Why do you stand at the door?

Information

The Jewish Museum of Belgium, Brussels

17.06.2022 — 01.01.2023

Curated by Patricia Couvet

WHY DO YOU STAND AT THE DOOR? presents work by the Ukrainian artist Nikolay Karabinovych (°1988, Odesa) as well as a selection of publications housed in the Yiddish library of the Jewish Museum of Belgium. The exhibition juxtaposes the history of migrations of Eastern European Jewish communities with that of cultural publications written in Yiddish in the 1920s and 1930s.

This project is the result of research carried out by the artist in the museum archives, in association with curator Patricia Couvet (°1994, Paris) and the Jewish Museum of Belgium.

About the project

The title of the exhibition WHY DO YOU STAND AT THE DOOR? is taken from the Yiddish folk song 'Lomir Zikh Iberbetn' (Let's Make Up).

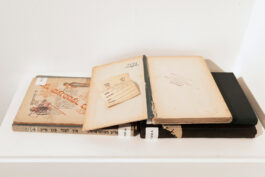

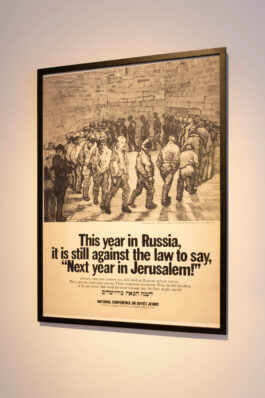

The lyrics are a call to love, as well as a reference to the fear of the other's departure. The line is used here as a metaphor for the compulsory and successive migrations of Eastern European Jewish communities to the gates of the West. A forced nomadism, which can also be read on the first and last pages of the Yiddish cultural productions housed in the Jewish Museum of Belgium. Some were published in Kyiv, Warsaw, Vilnius and then sealed in Johannesburg, New York and are now kept in Brussels, Ghent or Antwerp.

These seals are a starting point for a poetic exploration of a fragmented collective memory, within which the women poetesses testimonies reconstruct historical intervals of displacement, a history of migration omitted by books presenting national narratives.

The history of Yiddish publications is inextricably linked to those who speak the language. Its use has survived the qualifications of zhargon thanks to a culture that transcends notions of, national borders and cultures. The Judeo-Germanic vernacular was transformed by migrations through Eastern Europe by those who practised it from the Middle Ages in the Rhine Valley to Birobidzhan.2 Yiddish is an inherently diasporic language.

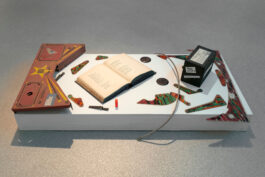

in the project space of the Jewish Museum of Belgium, the works of Nikolay Karabinovych subtly combine references to Jewish culture and its representations in literature, music and audiovisual archives

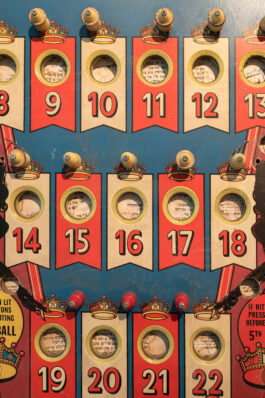

In an active and non-exhaustive voice, Nikolay Karabinovych questions the writing of a history fragmented by migrations, the knowledge produced by the diaspora and the meaning the archives of the Jewish Museum of Belgium are afforded today. Objects placed on graphic-like drawings in museum windows blur the differences between the artist's work and the archives selected from the Yiddish library. The artist asks the question of how we should look at the preserved objects, their status as artefacts in an ethnographic writing of Jewish culture and the institutional narratives surrounding them in Brussels, Moscow or Odesa. The door is used as a metaphor to open up new readings, but also as a reference to the history of the Jewish Museum in Belgium, whose door remains a reference to a heinous anti-Semitic event.

In this space, the artist's personal stories are linked to those of the displaced authors. The exhibition juxtaposes literary archives and photographs representing the Jewish diaspora with fictional writing proposed by Nikolay Karabinovych.

The pages can only be understood by those who can There are only a few people left in Belgium who can do so. From these books, the artist was able to decipher some of the covers, which are sometimes written in Russian or Ukrainian, and the stamped seal of the libraries. Nikolay Karabinovych's artistic approach values what is not perceptible to each visitor, in order to leave room for the imagination.

The selected and presented texts by authors such as Madye Molodowsky

(°1894, Biaroza - 1975, Philadelphia), Myriam Ulinover (°1890, Lódé - 1944, Auschwitz), Rachel Korn (°1898, Podliski - 1982, Montreal) are rendered timeless by their reading today.

They testify to the emancipation of Yiddish verse and prose in the context of the 1920s and 1930s, before the historical recurrence of exile and distance. Their study provides a framework for understanding the personal experiences of forced migration in the past and present. How to express the trauma of displacement when the language in which they are expressed has almost disappeared?

In 1937, in Chicago, the author Madye Molodowsky, born in what is now Belarus, wrote (freely translated):

The wind stole the last word.

A movement of the lips,

A beckoning hand.

The distance covered my town

My bleak nest

Mv street -

My pain and my flag.3

The experience of Nikolay Karabinovych and the history of his family are superimposed on a background of historical sources.

They are to be found in Kyiv, a nerve centre publications of the "Kultur Liga’’, organisation4, as well as in Odesa, the Black sea town where the author of Jewish origin Isaac Babel came from. This author, who passed through Brussels in the 1930s to join his fiancee Eugénie, is one of the underlying references in Karabinovych's work.

Babel's works are as realistic as the cruelty of the times in which he lived:

"Governors and circulars give the poor Jews of Odesa a hard time, but it is difficult to dislodge them, as the origin of their situation goes so far back. Not only will they not be dislodged, but there are many lessons to be learned from them. It is largely thanks to their efforts that the light and airy atmosphere of Odesa has developed.” 5

Press

Bruzz.be (tv reportage)

Related matirails

Project credits

Design

Callum Dean and Tjobo Kho

Photo

Photographed by Isabelle Arthuis

Special Thanks

Bruno Benvindo, Philippe Blondin, Sophie Collette, Barbara Cuglietta, Anna Fernandez, Laia Lozano, Marianne Martichou, Caroline Roure, Olivier Vander Perre, Philippe Straus and the team of the Jewish Museum of Belgium, and also Alexandra Tryanova, Sasha Pevak